Finding My Cultural Identity

by Tsering Khando

Clifford Geertz in “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight” states that, “The culture of a people is an ensemble of texts, themselves ensembles, which the anthropologist strains to read over the shoulders to whom they properly belong." The phrase, “strains to read over the shoulders to whom they properly belong," applies very much to me. In this case, I am the anthropologist figuring out a culture. Belonging to a certain culture has always been an issue for me. As a child born and raised in Nepal, it was hard for me to understand that I was anything but Nepali. When I moved to New York City, I completely absorbed the American culture. The concept of Tibet flew right over me. I was assimilated; I had no idea what Tibet was or where. To me, having an identity meant being associated with a certain country, so my failure in acknowledging my Tibetan heritage was simply due to the fact that there was no recognition of Tibet as a country. “The problem of producing a national or ethnic identity in the absence of a recognized territorial base is one of the most interesting and challenging issues of contemporary life."

When my mother thought I was at an appropriate age to learn about our country, I resisted. I was often angry having to spend an extra hour learning a language that was lost on me or visiting temples to pray to gods whose appearances just frightened me. I just wanted to go out and play with my friends. My anger was heightened when she took me to see His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama on my birthday. She told me I was blessed to have the opportunity to see him, but to me it was just plain torture. As I grew older, I became more aware and interested about my culture and family history but I was still lacking major details about both my family history and Tibetan history. When people would ask me, I would say I was Tibetan and most of the time they would have no idea where that was and would ask me more. When this happens, I realize that I only knew the most basic information and really needed to learn more about my culture.

Figure 1. Lhasa from the Pabonka Monastery. 2011. N.p

Inside the Motherland and Flight Outwards : My Mother’s Family

When my great grandmother from my mother’s side, Gesang Norzin was born sometime in June of 1936 in the capital city of Lhasa, Tibet had been in a truce with Nationalist China after their defeat from the Sino-Tibetan War. The Sino-Tibetan War began in 1930, under the regime of the 13th Dalai Lama, when the Tibetan army invaded Chinese territories of Xikang, Yushu, and Qinghai in dispute over monasteries. While she grew up during the rare era of truce between the always-clashing states of China and Tibet, what would come to happen in ten years was the biggest conflict between the two countries.

During the period between 1949-1950, the communists in China, with the support from Joseph Stalin, had successfully gained control of the government. The newly established administration sent troops to invade Tibet. “A treaty was imposed on the Tibetan government in May of that year, acknowledging sovereignty over Tibet but recognizing the Tibetan government’s autonomy with respect to Tibet’s internal affairs."

Seven years after being seized by China, my great grandmother, then 22 years old, had an arranged marriage. My great grandmother has kept her maiden name even after marriage, since it was not part of Tibetan customs to change names after nuptials. However, she did have a family name that relatives from my mother’s side still identify with. This name, Guza, was passed down from her mother’s family and came from the land that they were tied with. Before invasion of China in 1950, family names were of great importance in Tibet since they represented where you came from. In an informative webpage called, “The Rise and Fall of the Tibetan Nobility”, there was mention of land. The piece read, “It seems that what was important in Tibetan tradition was land and not blood lineage, the clan and not the individual. It is very difficult to trace back the history of a Tibetan clan because of absence of original family records. Details of people and events of even a few generations ago are quite vague. In some historical records, one often comes across the names of residences only." However, after the abolishment of land owning by China, Tibetans stopped using family names since they were no longer of value.

As the new rule of the Chinese government went on, more and more opposition of Tibetans towards the administration was created. One of the main reasons for defiance was due to the fact that “as the Chinese consolidated their control, they repeatedly violated the treaty and open resistance to their rule grew, leading to the National Uprising in 1959 and the flight into India of Tibet’s head of state and spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama” (Tibet Office). The National Uprising in 1959 was the biggest uprising against the Chinese government that had ever taken place. As the website mentioned, it was especially noted for the successful escape of the 14th Dalai Lama to India, who is now exiled from Tibet.

Although the National Uprising made way for the flight of the Dalai Lama, in retrospect it failed and even increased brutality of the government towards Tibetans. Due to the increased rebellions and resistance, the Chinese government had started using houses as prisons for those who rioted or opposed. One of their main prisons in the capital city of Lhasa, the Guza Prison, was the home where my great grandmother grew up, before they seized the land.

Figure 2. My grandmother, Tashi Yangki, with my two uncles, Tenzin Dechen and Tenzin Tselhen in Tibet. c. 1976.

No longer being able to deal with the strict laws and restriction of freedom of the Chinese government, my great grandmother escaped Tibet to Dharamsala, India in 1986 with my mother and her three brothers, my uncles, who were in their teenage years. Her daughter, my grandmother, stayed behind with her husband back in Tibet. They carried pounds of tsampa, barley in Tibetan, as food and not much else. As was the method, they drove in a car towards the border of Tibet and then met up with other groups of Tibetans. They, then, trekked across mountains in order to reach Sikkim. Some did not survive to make it towards Tibet’s border, as issues such as severe frostbites and viral colds occurred.

After the escape of the Dalai Lama, about 75,000 Tibetans followed suit as refugees. (Samphel 239) One of the few ways Tibetans have escaped Tibet have been through have been Bhutan, Nepal, and India. The group of Tibetans with whom my family was with, took the route of going from Lhasa to Sikkim, one of Tibet’s borders with India.

Figure 3. Map of Borders. Asia Times Online. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Apr. 2015.

The place where my family was escaping to, Dharamsala, had been granted as the location by the Indian government for refugees. It was where the Dalai Lama set up his administration and the headquarters of the Tibetan government in exile. “The main concern of the Dalai Lama and his administration at the beginning of their tenure in exile was the rehabilitation of thousands of Tibetan refugees. The most effective rehabilitation strategy which was agreed upon by the Tibetan administration, the Government of India, and the concerned aid organizations, called for the creation of permanent agricultural settlements throughout India.” In order to combat loss of culture, in exile, the Tibetan government decided to make modern education the “very weapon to defend and preserve the religious and cultural heritage of Tibet, which in old Tibet it was thought to be the undermining force of these aspects of Tibet’s social and political structure.” Therefore, in 1961, there was an establishment of the Central Tibetan Schools Administration and it became part of the Indian Ministry of Education.

After escaping to Sikkim, my family traveled to Dharamsala and settled there. Because of the Tibetan initiative of preserving culture, my great grandfather was given work as a teacher of Tibetan language. Teachers and their families were given rooms to stay in so that is where my family ended up living. Since their mother was back in Tibet, my great grandmother acted the role of a parent and raised my mother, as well as her siblings, until she (my mother) left for Men-Tsee-Khang, a Tibetan medical school in 1991.

Upbringings & Movement of My Grandfather and Family

While my mother grew up in the capital city of Lhasa, my father and his family lived in Dingri, a town in southern Tibet. According to an article in The Tibet Journal called, “Reexamining Choice, Dependency, and Command in the Tibetan Social System: “Tax Appendages” and Other Landless Serfs”, Melvyn Goldstein explains that Tibetan hierarchy prior to 1959 was made up of three main social groups: miser (common people), sger pa (nobility), and monks (86). These social groups were divided into high (high ranking monks, noble families), middle (land-owners, minor government officials), and low divisions (blacksmiths, butchers). My grandfather, Trinley Gyatso, was born in 1935 to a low middle class family of nomads. However, all his luck changed when, according to, “Biographies: The Lineage of Trinley Gyatso Lama, the Bardok Chusang Rinpoche”, a biography of grandfather (legitimacy confirmed by him to me), “at an early age he was discovered by a select party of Lamas who were searching for the reincarnation of their former Abbot.

Through meditation, they had had a number of visions and indications, informing them to look for the rebirth of the Abbot of their monastery in the region of Bardok, which is in the county of Dingri, not far from Mt. Everest. When they found the child, they put him to the test. A number of objects were placed in front of the boy and he was expected to pick out just those items which had been his in a previous life: a rosary, a particular cup, some clothing. Rinpoche (incarnate of a highly respected teacher) knew at once which were "his" possessions, and which were not. He also knew precisely what the Lamas were doing, and told them in detail about his former monastery." This technique was highly common in Tibet and even used to find the 14th Dalai Lama.

Figure 4: My grandfather, Trinley Gyatso, in his late twenties at the Chusang Monastery c. 1964

After confirmation, my grandfather at the age of eleven, now called “The Venerable Bardok Chusang Rinpoche Palden Mipham Tsuthop Trinley Gyatso Lama”, reincarnation of an eleventh century Indian yogi-saint named Pa Dampa Sangye, the founder of a system of spiritual practice known as Chöd, was sent to be groomed in the Chusang Monastery in order to take on the role as the head.

My grandfather married my grandmother, Dorjee Dolma, in 1962. She is pictured on the right side of my grandfather in figure 5. They had four daughters and two sons together. My father, Sonam Rinchen, was born in January 1st, 1965. Soon after, Mao’s Chinese Cultural Revolution took place. In “Conflict and Social Order in Inner Asia”, Fernanda Pirie states that little has been written or known the violence of the Cultural Revolution in Tibet. According to PBS, “During Chinese Cultural Revolution, Tibetan temples, monasteries, libraries, and scared monuments destroyed or made into state museums."

The initiative was part of the anti ‘Four Olds’ campaign that called for new prohibitions on all forms of religious practice. Pirie states, “Despite the demise of organized religion and closure of monasteries and nunneries after 1959, individuals had been permitted to continue to practice religion on a private basis in their homes. However, not only had that ended with the onset of the Cultural Revolution, but Red Guards had systematically searched houses to collect and destroy religious objects, such as statues and prayer wheels, while also mobilizing villagers to physically tear down temples and monasteries."

Fearing for the safety of his family, my grandfather, my father now ten years old, and his family managed to escape the persecution and become refugees in the Solukhumbu District of Nepal in 1975. Since Dingri was in the south, it was not that far from the border so the escape was a success but unfortunately, Chusang Monastery was destroyed during the revolution.

My grandfather Trinley Gyatso and family after relocation to Solukhumbu c. 1978

In 1990, my father left for Dharamsala where he studied medicine in Men-Tsee-Khang, the same Tibetan medical institute my mother left for, one year later. At the same time, my grandfather and the rest of his family moved to Kathmandu, the capital city of Nepal. There, in Jorpati, he bought a house and built a new Chusang Monastery next door. Eventually, in the early 2000’s, my grandfather was able to send money back to Dingri and rebuild the original Chusang Monastery that was destroyed after the Cultural Revolution.

Leading A Business Inside Foreign Land

According to Philp Denwood in “Tibetans and Their Carpets”, Most Tibetans in Tibet had the occupation of being farmers, part of the lower middle social class. Town life was very scarce. They lived near their fields in widely separated river valleys. “The vast intervening stretches of steppe and mountain are grazed by livestock belonging to the farmers or to small bands of tent- dwelling nomadic Tibetans” (Denwood 67). The upper class in traditional Tibet was composed of monasteries and aristocratic households who were the main source of wealth and higher culture. “Material conditions of life and many features of material culture are very reminiscent of what may be found in the arid lands of western Asia and the Middle East. Life is simple and rough for the majority, but overpopulation is not a problem and there is enough food and land to go round”. Although my grandfather’s installation as a head of a monastery put him and his family into the upper class division, they quickly shrank into lower middle class after their escape to Nepal.

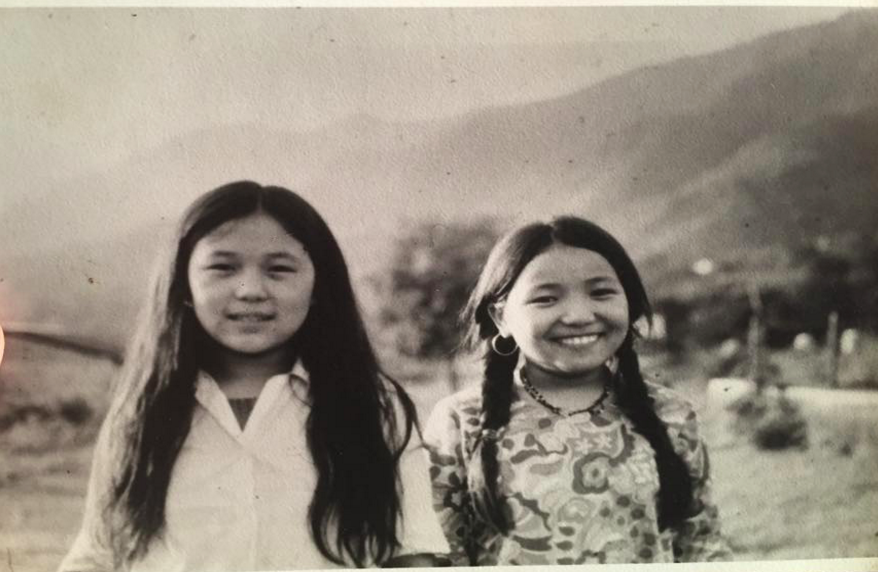

My aunt Nawang and Nangsa (left to right), living as refugees in Solukhumbu, Nepal c. 1981

According to Tom O’Neill, in his article “Ethnic Identity and Instrumentality in Tibeto-Nepalese Carpet Production”, “The small number of refugees who crossed into Nepal after the invasion of Tibet in 1959 constituted a significant change in what had been a consistent flow of peoples, trade, and religious ideas between the Tibetan plateau and the Nepalese hills. Nomads and Himalayan traders routinely crossed the Himalayas for hundreds of years, but after the boundary between Nepal and Tibet became politicized after 1959, Tibetan refugees became liminal residents in a country in which millions shared their language, religion and cultural heritage."

No longer being wealthy and immobilized in foreign land permanently anymore meant that even my aunts, Nawang Chusang and Nangsa Chusang, who previously held no jobs, had to start finding one in order to support their family, especially since much of family money was spent on rebuilding of the Chusang Monastery in Kathmandu.

One of the traditional Tibetan crafts is carpet weaving. The carpets are used by Tibetans on top of seats or beds, contrasting to other cultural use of carpets, which include wall hanging or simply used on the floor. During my interview, my aunt Nawang said, “Since we already knew what went into making carpets, as was common knowledge among many Tibetan women, me and your aunt Nangsa thought it would be the best way to make money." She stated that their ability to work was even limited by the fact that they were on foreign land as refugees with no previous experiences and no citizenship.

Therefore, like many refugees, carpet weaving became the only business. O’Neill mentions that, “the limits of Tibetan refugees inside Nepal has important consequences for the ability to accumulate capital, as ownership of property – including enterprises – is restricted to naturalized Nepalese citizens. The only real barrier to a refugee small producer is that their enterprise cannot be registered with the Nepalese Department of Cottage and Small Industries (DCSI), but they are still free to run their businesses and subcontract weaving orders from carpet exporters. Without registration with the DCSI, however, they cannot export their carpets on their own, and non-naturalized Tibetans cannot own property that could be used to expand or diversify their businesses. For the many Tibetan refugees who had extensive export businesses and properties, the lacks of citizenship posed a dilemma, as they had to either try to become naturalized Nepalese citizens (an improbable and expensive process), or obtain a Nepalese partner with whom to register the company."

In order to support themselves, Denwood also mentions the struggles of Tibetan refugees having to seek employment and income of their own. “The Tibetans in India have been thrown from a society broadly comparable to that of medieval Europe into a comparatively modern, democratic, industrializing country. Tibet's economy was, in modern terms, primitive, consisting almost entirely of subsistence agriculture with a little trade in farm products and minerals, which were exchanged for small quantities of imported foodstuffs and manufactures. Other wants were filled by local craft industries such as carpet weaving. The administration of the government and the large monasteries was relatively simple and adapted to a stable, familiar situation. Large, complex organizations demanding special skills and disciplines, such as exist in, for example, China, Japan and India, were absent from Tibet” (Denwood). Unlike most Asian countries that have, through Western influence, “at least a nucleus of technically trained personnel”, there was no such development in Tibet.

Denwood states many problems Tibetan refugees such as my family had to face in Nepal in regards to employment. Tibetans have been unable to compete against Indian industry with its ultra-cheap labor and superior organization. There have been other problems in their new situation as well.

Economic ones were the most pressing, at least in India and Nepal where food and employment are often acutely short even for the native population. Denwood states, “Although refugee conditions are far from Utopian, they are generally well up to, often better than, average standards prevailing among surrounding peoples. Solid, well-roofed houses, adequately spaced and provided with electricity, water and sanitation are the norm rather than the exception in Tibetan refugee camps. Food is, at worst, sufficient for survival in a tolerable state of health. Education for the children, and rudimentary medical care, are more often than not available. Thus most Tibetan refugees are certainly spared the fearful plight of the Indian urban poor or the Bangladesh refugees."

Another issue prevalent is marketing. My aunts created their workplace in the basement of our house in Kathmandu. They hired locals to weave the carpets and sold them in the local area due to the restrictions of exportation. However, most of demand for carpets lay overseas, specifically Western Europe and America. But, they did not yet have the money and contacts to sell their carpets for profit from overseas. The local weavers were being paid something like £5-£10 per month, $10-$15 dollars in America, which is the time it takes to make a carpet. My aunt Nawang agreed with these numbers and told me that marketing in a local area left little money to be given as salary to the workers and thus those were the wages. Denwood remarks, “At least $7 is absorbed by the cooperative marketing organization, which gets through the formidable amount of paperwork required to export anything from India. By the time transportation costs have been paid, the finished carpet, size six feet by three, will cost £30-£40 in Europe. On the West Coast of the United States, Tibetan carpets are slightly undercut by similar carpets of high quality woven by Chinese ex-servicemen in Taiwan.”

Soon after the establishment of my aunts’ business, the popularity of Tibetan carpets picked up through many factors such as tourism and my aunts partnered with a local Nepalese exporting company in order to sell overseas. O’Neill states that, “In the forty years since the invasion, the production of carpets has grown from a cottage industry to one of Nepal’s most important export industries, and the Tibetan refugee community has been thrust from its liminal status to the center of Nepal’s economic life." My aunts were now able to make a lot of money and eventually become the main income supporters of our household in Nepal.

Since the mass migration and uprising in 1959, the design of refugee carpets has changed. Most Tibetans have transitioned into using Indian wool, which, especially after treatment with synthetic dyes, is harsher, stiffer and rougher than the Tibetan wool. The number of knots per square inch has been increased and the pile thickened a little, so that there is much more wool to the square foot of carpet than before. This makes the carpets much harder in wearing and also harder in touch – stiffer carpets are more suitable for use on floors by the new class of European and American customers. “Tibetan refugees in India often cover their charpoy beds with carpets, nowadays made exactly the right size to cover them.. Many of the refugees were from the carpet-weaving area of Tsang which is just over the border from Nepal and Bhutan, and sufficient skilled weavers arrived to make possible the re-establishment of the craft on new lines."

Generally, shades have been toned down, again in response to modern Western tastes. Pastel shades are often seen, and new color schemes with large areas of green and white are a sharp departure from tradition. All sorts of non-traditional motifs, although rejected from the Tibetan culture, have been embraced. Motifs such as snow lions, Buddhist symbols and representational scenes now being used. Denwood says, “The results of this sudden freedom from the restraints imposed by natural dyestuffs and traditional canons are often unhappy - though this is by no means always the case, and the carpets always remain distinctively Tibetan products. The size and specification of the carpets has been standardized to a remarkable degree now that different settlements are competing against each other” (73). He concludes, “Altogether, Tibetan carpet weaving today enables growing numbers of Tibetan refugees to support themselves, and helps in a small way to conserve their rich but hard-pressed culture."

Conclusion & Meta-Narrative

This research project, to me, was one of the hardest assignments that I had ever worked on because I went in knowing almost nothing about my family history. However, I am extremely glad for it because I came out learning so much about both sides of my family. I struggled a lot of times in finding information from the oldest people in my families because my grandfather and great grandmother did not remember much, therefore a lot the dates I put down are estimates. Also, it was hard to ask the rest of my family for information because they were always working and did not live near me. However, I feel as though what I learned from my interviews with my grandfather, great grandmother, and aunt was extremely valuable for the assignment and my own personal knowledge.

There were so many things that I was surprised to learn such as that my mother's original home as a child in Lhasa is now a Chinese prison. I was also fascinated by the fact that my grandfather was a incarnation of a highly respected Tibetan religious teacher. There are pictures of this yogi in black and white that I always notice when I visit my grandfather's house and I never knew who it was. Through this research, I came to know that it was pictures of the person who he is allegedly the reincarnation of. The webpage on my grandfather that I found said that my grandfather was one of the only few true Tibetan yogis left and I was so surprised because I had always seen him as just being this kind hearted old man that consistently gave me pocket money as a child. To be honest, I also felt kind of guilty because there was so much history and experience of Tibet in him yet I never was curious enough to ask him about any of it.

I was extremely surprised that even though I lived with my aunts in Kathmandu, I never noticed that we had a carpet business in the basement. My cousins had known about it when I asked them but the could be due to the fact that they were much older than me to notice these things. When finding out about the carpet business, I did not know that it was a common thing among Tibetan refugees, written about in many scholarly essays, which is what I learned from research. I wonder many things about this business such as why my aunts decided to end it and how they were able to operate it when they moved to America, many questions they could not answer at this time. Growing up in Nepal and then America, I struggled a lot with finding my identity. I learned Nepali and English language before my own mother tongue, Tibetan. Being born in a foreign country, I was extremely confused about my culture and where I belonged. It was not easy to consider myself Tibetan because as a child I used to think that I certainly could not be Tibetan because Tibet as a country did not exist. I certainly did not want to tell other people in classes that I was Tibetan in America because I was embarrassed that our country was taken over and technically did not exist in eyes of the world.

Every time I did tell someone, they would just look back at me strangely and either ask, "Where is that?" or "Isn't that part of China? So you're Chinese? But you don't look Chinese". Therefore, it was just easy for me to say I was Nepali since I was born there. In Nepal, I was busy assimilating with the Nepalese and in America, I was becoming an American. Since my family were struggling to make a living, they did not think much about teaching me about Tibet. The closest I had gotten to learning was reading "Tin Tin goes to Tibet" in Kathmandu. Therefore, history did not mean much to me. It was something I was never curious about. The Tibetan part of my identity was always suppressed. As I grew up in America, I was starting to become aware of Tibet and its struggles. However, I never asked about it to my parents because I knew there was a lot of sadness and destruction in that tale that I did not want them to remember again.

After working on this project, history has come to mean so much to me. Learning about my family history, I realized there was so much of actual history tied into it. Understanding my ancestors and their past really helped me in finding my identity and what it means to be a Tibetan. Both sides of my families have been through a lot in their past and I am glad for this assignment because I am now able to tell future generations about this. Assimilation was not only an issue for me but every second and third generation Tibetan children who grew up in foreign land. I now realize that if I do not value history and culture of my people then it will slowly disappear as many more Tibetans suppress their identity in place of another's. I am grateful for this project in teaching me about my own identity and helping me appreciate it. I am now extremely proud to be Tibetan because even though we no longer have a homeland and have been through so much struggles, we are still surviving and will continue to survive.