Khaal, The Tattoo of Afghan Womxn

I started wearing khaal I would mark with henna as a way to get closer to my Afghan identity. Henna is a paste made out of a plant that (temporarily) dyes your skin like a tattoo would, and is used as a common ceremonial and cultural practice throughout South Asia and the Middle East. Permanent tattoos are not so much taboo, more so looked down upon within Afghan culture for a few reasons.

Firstly, Afghanistan is an Islamic country, and many believe that the tattoo ink doesn’t allow you to be fully cleansed for namaz (prayer). Islamic countries also see tattooing as a sin, which I will explain more about later.

The other is that Afghan culture is rooted in reputation; what someone else will perceive you as. You represent your whole family, so people try to avoid anything with a negative connotation out of fear of what others may think.

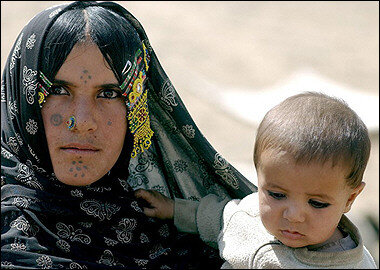

Khaal is different, though. It has a long history that stems from the villages in pre-Islamic times. This remains popular in tribes and small villages today, specifically in the Pashtun region where my family is from.

Khaal literally translates to dot because khaal is mainly done in the form of green dots and circular shapes. It’s most commonly done on one’s face on their chin, cheeks, foreheads, and even on the back of the hands. Tradition has it that elderly womxn of the tribe or village will use a method similar to stick-and-poke to mark the younger girls (around ages 14-20).

As mentioned earlier, Islamic societies see permanent tattoos as sin since many scholars believe and teach that altering God’s creation in any form is haram (forbidden). However, it is worth noting that there is no explicit verse or chapter within the Qur’an that states that permanent tattoos are haram or a sin.

Because of the consistent back and forth on the topic, it has caused some dangerous repercussions for Afghan womxn with khaal. This practice has mainly continued within the villages, where access to Islamic schooling and teachings is rare to come by. Most womxn don’t realize that this process could possibly be a sin, so for those who don’t decide to keep it, they often remove the tattoos with acid—a dangerous practice that leaves permanent scarring. There is little to no proper medical tattoo removal services in Afghanistan, and for most, they cannot afford it; acid removal is their only option.

However, the narrative around tattoos has been shifting in the recent years. Afghanistan gained its first female tattoos artist, Soraya Shahidy, in the past year. Shahidy studied her practice in Turkey and Iran, and she decided to bring her talents back to Afghanistan to offer space for folks to express themselves creatively through the art of tattoo. Her shop in Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital city, also offers lash extension and manicure services which were previously outlawed by Taliban rule.

Slowly but surely, khaal is reowning its mark of tradition within Afghan society. Maybe in the coming generations, we will also see different forms of tattooing become common practice within the country as a whole.

Farial Eliza (she/her) is a twenty-one year old Bay Area native, occupying unceded Chochenyo Ohlone land. She is a writer, poet, creator, storyteller, self-proclaimed healer and educator to the communities she serves.