On "Death Note," Morals, and Existential Crises

by Lucy Zhang

One of the most unfathomable things in this world is how insignificant one’s self truly is. we may be vaguely aware that our lives are mere specks of dust in a whirlwind of chaos, but the fact that our presences are quite insignificant relative to the world rarely hits home, and I’m not sure it ever will for most. We humans, and perhaps all living creatures, live closest to ourselves—the most tangible entity that we are exposed to continuously day in and day out. It’s probably easier thinking this way too, otherwise face some existential crisis.

Death Note’s protagonist Light Yagami is an example of one of the extremes on this spectrum. He is an all-around perfect student—athletic, smart, handsome, and outwardly kind. He is an actor and a liar with a superiority complex, and just before the plot picks up in the anime, his attitude towards life is that of a person playing a meaningless game with all its cheat codes. Light Yagami finds that life is boring, and more than that, it is a rotten place full of despicable people.

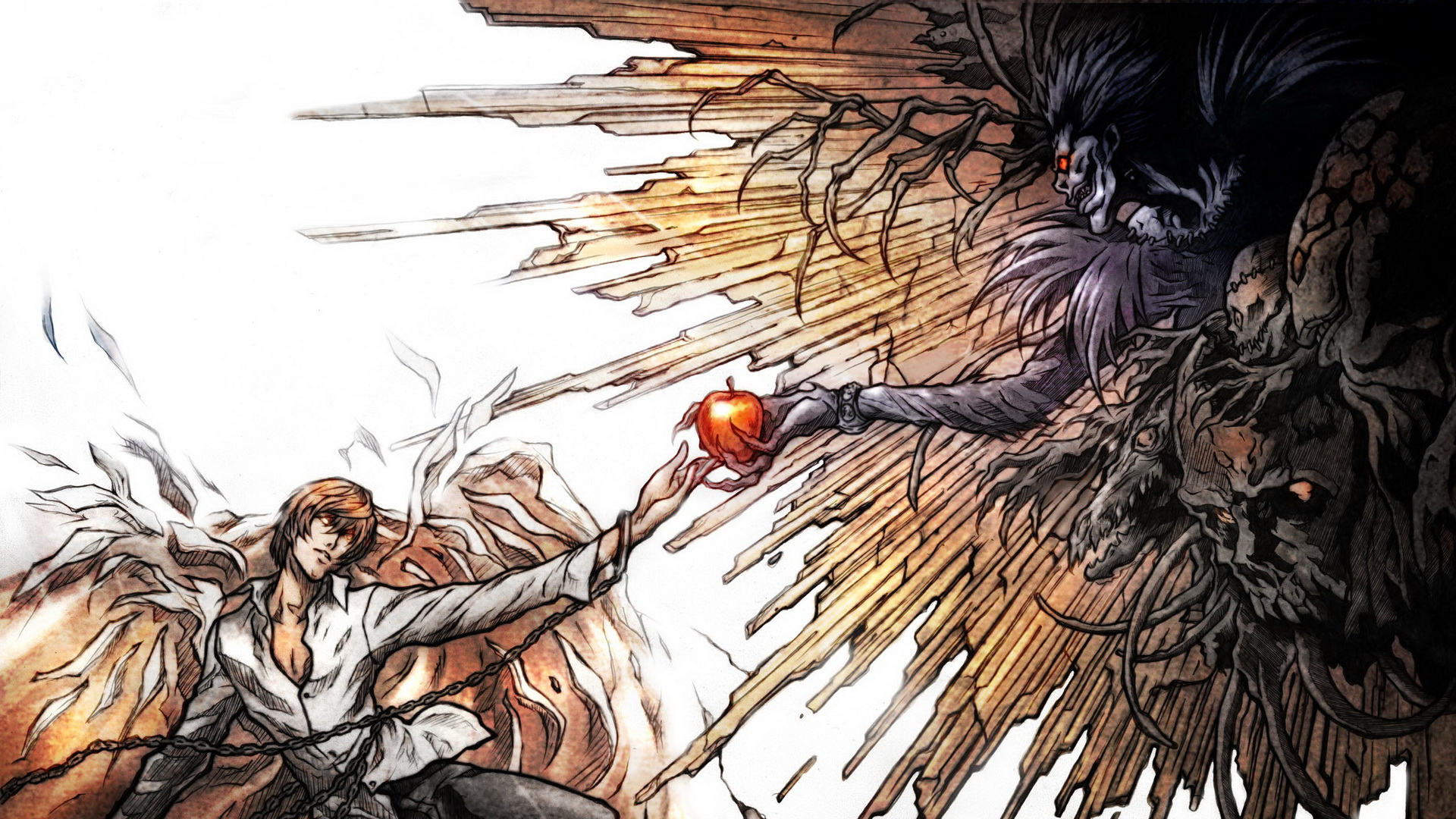

But then, he finds a Death Note, a notebook that shinigami, also known as death gods or grim reapers, use to kill people. The Death Note simply requires the owner to write a person’s name in the notebook in order to kill that particular person. The notebook kills a person through heart attack if no cause of death is specified. When Light finds the notebook, he doesn’t behave like one might expect from a show meant to entertain. Rather than completely shun the notebook or foolishly experiment with it out of curiosity, he behaves with caution and intelligence from the beginning. He ultimately decides to kill a criminal whose life no one would care about. This decision quickly escalates and lays the foundation for Light’s god complex—he soon believes he can purge the world of evil by killing criminals.

L, an inhumanly intelligent detective and prodigy, discovers the peculiar death trend of criminals dying from heart attacks and tackles the case. The show plays out to be an intellectual cat and mouse chase between Light and L, with the roles of cat and mouse constantly shifting as to whom they represent. While many viewers look at the show and see Light as the “bad guy” and L as the “good guy”, they soon find that it isn’t so simple.

The dichotomy of good and evil is only one of many that we use to simplify life.

It’s easy to say that killing anyone, even if they are a criminal (a death row criminal at that) is a crime. In many of Light’s internal monologues, he speculates that the moral righteousness embodied in that idea is merely a facade—while humans might outwardly voice that all killing is wrong, most of them likely think otherwise. Even on social media today, an article about a criminal who has committed a gruesome act is decried by commenters demanding “justice”—often the death penalty. In other words, they are unsurprisingly hypocrites.

Justice is a central theme to Death Note. The two central characters are warped by a sense of justice that, in reality, is a product of their egos. Light, whose solipsistic view has graced him with a god complex, and L, whose intelligence makes him completely socially inept, both see themselves as embodiments of justice. Light’s personal view of himself as justice is not so complicated—he kills criminals and plays god through determining other's’ fates, his own noble goal of purging the world of all that makes it rotten. L, however, is not actually majorly driven by a desire to right a wrong or end the killings. Rather, as a prodigy and genius, he is driven by the thrill of solving a mystery and the case of Light and the Death Note provides a rare challenge to his intellect, one he refuses to accept defeat in.

L and Light are both “monsters”. By monster, I refer to a human who deviates emotionally, socially, and intellectually from the convention. As L put it:

“There are many types of monsters that scare me: Monsters who cause trouble without showing themselves, monsters who abduct children, monsters who devour dreams, monsters who suck blood... and then, monsters who tell nothing but lies. Lying monsters are a real nuisance: They are much more cunning than others. They pose as humans even though they have no understanding of the human heart; they eat even though they've never experienced hunger; they study even though they have no interest in academics; they seek friendship even though they do not know how to love. If I were to encounter such monsters, I would likely be eaten by them... because in truth, I am that monster.”

The irony is not lost. While L and Light view their worlds strictly in black and white—defeat or be defeated—their viewpoints color the show in an interesting way that pits monster against monster.

An peculiar phenomenon occurs. Even though neither is a conventional harbinger of good (unlike the clear cut light and dark in the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter series), the viewer inevitably starts to root for one of the characters. The urge to side with one of the main characters creeps on insidiously. In some ways, this favoritism is extremely revealing of the human desire to simplify. Once a favorite is selected, everything else is disregarded in favor of loyal support of that chosen one and seeing their downfall is of utmost devastation.

But favoring a character in Death Note is almost a requirement when watching the show. When one character is portrayed as borderline evil and the other as a sociopath, expecting the animation director to bluntly hint at the side you should be rooting for is asking for too much (and such a move might have moral implications on the animation studio).

So viewers pick a side, unconsciously or proactively, because they need someone to follow and throw (often) irrational favoritism behind, if only to clean away the ambiguities and turn the show into less of an ethical and moral question and more into a thriller where all that matters is which character is left standing by the end.

Who the audience roots for is quite telling.

Some might compare L to Sherlock Holmes, both brutally honest sociopaths who view cases as games to solve. In fact, Sherlock is likely a bit more empathetic and “human” than L, who goes as far as to torture a suspect. But all in all, audiences as a whole support Sherlock in BBC’s Sherlock, which makes quite a lot of sense. Sherlock is the clear protagonist and he solves problems and saves people all while seeming cool doing it. Similarly, L is brilliant, proven especially so given the incredible fight he put up against Light, who has the unfair advantage of a supernatural notebook at his side.

I personally see L as someone who portrays far fewer “human” like traits than Light does. He is so far removed from human society, separated by his intelligence and social quirks—more extreme but not unlike Sherlock. The allure of these characters is that no matter what kind of challenge is thrown in their way, these types of characters will resolve it with witty deduction and moves. A character who seemingly can’t lose. A genius sociopath who hasn’t been torn down by society due to their deviations from the norm. These types of characters aren’t underdogs, but rather romanticized figures that we could never be. They are heroes whom we love to watch from afar but would hate to be friends with.

Light, on the other hand, is evil. The way that the color red is associated with Light (for example, his eyes flash red on occasion marking his mood or line of thought) leaves no room for question. He is manipulative and wears a perpetual facade as the perfect student and son, unlike the often blunt L. By all counts, Light is despicable and many fans of Death Note seem to agree about his inferiority.

The way Light’s character is crafted is methodical. He begins as a relatable high school senior in the first few episodes but gradually descends into a god-complex. In fact, most of the audience’s time with Light is spent learning about his tactical moves to circumvent the detectives rather than be exposed to all of Light’s moral shortcomings (although when those exposures do occur, they hit strong).

In unjustly simplified terms, I see Light as a human who chose the “wrong” path. At the beginning, he was simply a cynical and brilliant student who worked hard in school to get the best grades and had some semblance of a superiority complex (understandable, given that he was the smartest of his grade and well-liked). He wanted to change the world for the better, an ambitious feat that he had no means of achieving until he came upon the Death Note. And then he was corrupted by power, which ultimately led to his downfall (although he did outlive L).

In general though, people don’t like seeing someone who could be a normal student-next-door descend into a cold, calculating killer without a sign of remorse. More than that, people don’t like liars—it hits too close to home.

We all lie, whether it’s for little things or monumental things, almost everyone has smiled at someone they have no real affection towards and complimented someone for something they didn’t truly like. Regardless of intent, it is still a facade. Light is not unlike most of us who endeavor to keep up an image of ourselves that society expects or else suffer a number of social, economic, or political consequences. That’s what makes characters such as L and Sherlock so appealing—they maintain an integrity to be true to themselves without withering away in society.

But Light’s path is a path that many a human could have taken had they stumbled upon the Death Note. Sure, a less intelligent human would likely not last as long as Light did in the cat and mouse game between him and L, but there is certainly more than one justice-ridden human who believes in the death penalty. If L represents the type of human whom we are mystified by, than Light reminds us of the vulnerability to corruption and the depravity of a human being.

Of course, this dichotomy is a simplification, but it does explain to some extent the favoritism of certain characters. But what about those who favor Light, the supposed wicked soul, over L?

For one thing, Light isn’t all that wicked and the show makes an effort not to initially portray him as so by making his descent into a blind greed for power so gradual that once you’ve already taken a liking to him, it’s hard to reverse. Another factor too obvious to ignore is his appearance: Light is handsome and well liked by girls in contrast to L’s panda-like eyes and lanky, careless, and sometimes creepy physical appearance. Appearance is a critical part of Light’s facade, and unsurprisingly, it works on some of Death Note’s audience as well.

Curiously, the reason why many people despise Light is why others like him: his lies. The reassurance that not everyone is perfect inside and out is an incredibly powerful psychological tool. After all, who wants to admit that they think the world would be better off killing criminals who have committed significant crimes? In other words, Light is relatable. Not to everyone, but to certainly some.

Religious motifs play a significant but subtle role in Death Note. I liken L to an angel who has randomly been dropped out of heaven and Light to an angel who has willingly fallen from grace, tainted by human corruption. But in the end, Light and L are still only human with the same grounding weakness of mortality.

No matter how special someone might seem, the world remains pretty indifferent.

Both L and Light end up dead. L dies first at the (indirect) hand of Light. Light at the end of the show by a gun wound.

We see L die in the middle of the show, leaving another 20 episodes left and fading him into a faint memory. We see Light stumble with his mortal gun wound. That he would die so simply by such a human means paints him as pathetic and almost cringe worthy. In the end they both bleed red and there is no conceivable victory on either end. Both end up dead, leaving the world close to where it was prior to their epic battle of wits and lives—the same “rotten” world Light scorned before he stumbled upon the Death Note.

L’s death halfway through the show was disappointing but Light’s death was devastating. Even with the death of two “angels” so misplaced in this world, we as the audience are left to witness the futility of it all.

We simplify the world into a dichotomy of entities to makes sense of it to ourselves and our egos. In reality, it is more one massive, amorphous blur that no single mind can handle. So we focus on the small things that can be separated into our carefully crafted groupings. The majority of Death Note is seen through those divisions so pointedly crafted by the two feuding main characters and what they represent. But ultimately, we are forced to take a step back and temporarily set aside the debate of human morals and murder. As Ryuk, a shinigami and original owner of Light’s Death Note said, “All humans die the same, the place they go after death isn’t decided upon by a god, it is Mu (nothingness).”